Course Introduction

Welcome to the Basic Java to Advanced Spring Boot Backend Development Course — a six-month journey designed to take you from the fundamentals of Java programming to building full-stack backend applications.

This course begins with Core Java Essentials, covering syntax, OOP, and debugging skills, and later expands into JDBC, Spring Boot, REST APIs, Security, and Microservices

Mentor:

Dept. of CSE, Daffodil International UniversityLearning Goals:

- Understand the core concepts of Java programming.

- Set up the development environment for efficient coding.

- Learn how to structure, compile, and run Java programs.

- Build a strong foundation for advanced backend technologies such as Spring Boot.

Course Structure

- Duration — 24 weeks | 6 months

- Schedule — 3 classes per week × 1.5 hours each

- Total — ≈ 108 hours + 12 hours problem-solving sessions

Outcome:

After this introduction, you’ll clearly understand what Java is, why it’s relevant, and how this course will progressively build your development skills.

📚 Course Outline

Class 1 - Recording

▶ Watch VideoJDK & IDE Setup

☕ 1. JDK (Java Development Kit)

Used to write and compile Java programs.

Contains: JRE + compiler (javac) + tools.

💡 Example: When you type:

javac Hello.javayou’re using the JDK to compile your code.

⚙️ 2. JRE (Java Runtime Environment)

Used to run Java programs.

Contains: JVM + libraries needed to execute code.

💡 Example: When you run:

java Hellothe JRE runs your compiled program.

💻 3. JVM (Java Virtual Machine)

The engine that executes the compiled Java bytecode.

It makes Java platform-independent — the same code can run on Windows, Mac, or Linux.

💡 Example: The .class file created by the JDK is executed by

the JVM inside the JRE.

🧩 In short

- JDK = JRE + Development Tools

- JRE = JVM + Libraries

🔁 Example flow

- You write a program →

Hello.java - JDK compiles it → creates

Hello.class(bytecode) - JRE runs it → JVM executes bytecode line by line

Step-by-Step Installation

Set Environment Variables

Windows: Add JAVA_HOME to System Variables → point to JDK

folder.

Mac/Linux: Add to .bashrc or .zshrc:

export JAVA_HOME=/usr/lib/jvm/java-17-openjdk

export PATH=$JAVA_HOME/bin:$PATHVerify Installation

java -version

javac -versionOutput should display the installed version.

Installing an IDE

An IDE (Integrated Development Environment) helps you code faster and debug easier.

- IntelliJ IDEA: Smart and modern, ideal for professionals.

- Eclipse: Stable and used widely in enterprises.

- VS Code: Lightweight with Java extensions.

IDE Setup Checklist

- Open the IDE → Select New Project → Java Project.

- Set the project SDK to your installed JDK.

- Create a class file and write:

public class Hello {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello, Java!");

}

}Click Run — your first Java program is live!

Troubleshooting Tips

- “javac not found” → Check PATH variable.

- “Cannot find symbol” → Ensure file and class names match.

- IDE red underlines → Set the correct JDK path in project settings.

Java Structure

A quick, practical guide to how a basic Java program is organized—classes, methods,

the main entry point, packages, and more.

Minimal Program (“Hello, Java”)

public class Main {

// Program entry point

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello, Java!");

}

}- Class name:

Main(must match the file nameMain.java). - Entry point:

public static void main(String[] args)— where execution begins. - Output:

System.out.println(...)writes to the console.

Files, Classes, and Bytecode

- Write code in a file named after the public class (e.g.,

Main.java). - Compile:

javac Main.java→ generatesMain.class(bytecode). - Run:

java Main→ executes the bytecode on the JVM.

Note: A file can contain multiple classes, but at most one

public class, and its name must match the file.

Program Anatomy

| Component | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Package | Defines a namespace to organize related classes. | package com.example.app; |

| Import Statement | Includes external classes or packages for use in your program. | import java.util.Scanner; |

| Class Declaration | The blueprint that encapsulates data (fields) and behavior (methods). | public class Main { ... } |

| Main Method | The entry point of any Java program—execution begins here. | public static void main(String[] args) { ... } |

| Statements | Instructions executed by the JVM; each must end with a semicolon

(;). |

System.out.println("Hello, World!"); |

| Comments | Used to describe or explain code without affecting execution. | // This is a comment |

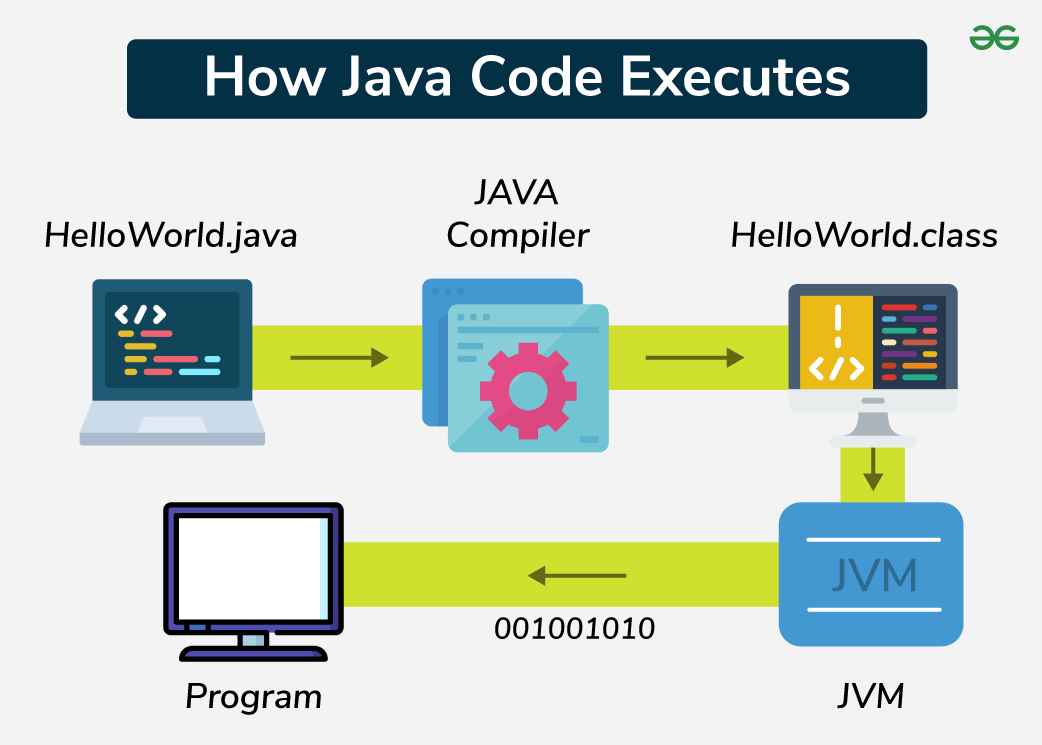

How Java Code Executes

This section explains the full journey from a .java source file to a

running program on your machine.

.class) and executed by

the JVM, which produces native machine instructions. Collected from

GeeksforGeeks.

-

Write Source Code (

.java)You create a file such as

HelloWorld.javathat contains Java classes and methods.public class HelloWorld { public static void main(String[] args) { System.out.println("Hello, Java!"); } } -

Compile with

javacThe Java compiler checks syntax and type rules, then converts source code into platform-independent bytecode stored in

.classfiles.javac HelloWorld.java # produces HelloWorld.class -

Class Loading

When you run the program, the Class Loader loads required classes (

rt.jar/modules, third-party libs, your classes) into memory. -

Bytecode Verification

The Bytecode Verifier ensures the

.classfiles are safe and follow JVM constraints (no illegal casts, stack overflows, etc.). -

Execution in the JVM

The Execution Engine of the JVM runs the verified bytecode:

- Interpreter quickly executes bytecode instructions one by one.

- JIT (Just-In-Time) Compiler detects hot code paths and compiles them into native machine code for better performance.

The JVM manages memory via the Heap and Stack, and reclaims unused objects using the Garbage Collector.

-

Program Output

After execution, your program produces output on the console, files, network, or UI.

java HelloWorld # → Hello, Java!

Key Terms

- JDK: Tools to compile and develop Java (includes

javacand the JVM). - JRE: Environment to run Java apps (JVM + core libraries).

- JVM: Virtual machine that executes bytecode on any platform.

- Bytecode: Platform-independent instructions in

.classfiles. - JIT: Compiles hot bytecode paths into native code at runtime.

Packages & Imports

package com.acme.app; // Directory: com/acme/app

import java.util.ArrayList; // Single class

import java.util.*; // Wildcard (use sparingly)

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

ArrayList items = new ArrayList<>();

items.add("Java");

System.out.println(items);

}

} - Directory structure mirrors the package path (

com/acme/app). - Prefer specific imports over wildcards for clarity.

Access Modifiers & Class Members

public class Counter {

// field (state)

private int value;

// constructor

public Counter(int start) {

this.value = start;

}

// instance method

public void increment() {

value++;

}

// static method (belongs to the class)

public static Counter ofZero() {

return new Counter(0);

}

// getter

public int getValue() {

return value;

}

}

- public: visible everywhere; private: visible only inside the class.

- static methods/fields belong to the class; instance members belong to objects.

- Use constructors to initialize new objects.

Naming & Style Conventions

- Classes/Interfaces: PascalCase (e.g.,

OrderService). - Methods/Variables: camelCase (e.g.,

placeOrder,maxCount). - Constants: UPPER_SNAKE_CASE (e.g.,

MAX_SIZE). - One public class per file; file name = public class name +

.java.

Compile & Run (CLI)

# From the folder containing Main.java

javac Main.java # compile → Main.class

java Main # runWhen using packages, compile/run from the project root:

javac com/acme/app/App.java

java com.acme.app.AppCommon Structure Errors

- Class/file mismatch: Public class

Appmust be inApp.java. - Missing

main: Applications need an entry point; libraries don’t. - Wrong package path: Package declaration must match folders.

- Visibility issues: Accessing

privatemembers from outside the class.

Next Steps

- Create a new project and a class with

main. - Print some text, declare variables, and call a helper method.

- Refactor into multiple classes to practice files, packages, and imports.

Class 2 - Recording

▶ Watch VideoData Types

In Java, data types define what kind of values a variable can hold and how those values are stored and manipulated in memory. Java is a statically typed and strongly typed language, which means:

- Every variable has a declared type at compile time.

- Type conversions are explicit or follow well-defined rules.

High-Level Classification of Data Types

- Primitive Types – built into the language, store simple values.

- Reference Types – objects, arrays, enums, interfaces, etc.

Primitive Data Types

Java has 8 primitive data types:

byteshortintlongfloatdoublecharboolean

1. Integer Types

Used to store whole numbers (no decimal point).

byte

- Size: 8-bit signed integer.

- Range: -128 to 127.

- Use case: memory-sensitive contexts (large arrays of small numbers, streams, file I/O).

byte b = 100;

byte min = -128;

byte max = 127;short

- Size: 16-bit signed integer.

- Range: -32,768 to 32,767.

- Use case: rarely used; legacy code and some binary data formats.

short s = 32000;int

- Size: 32-bit signed integer.

- Range: approx. -2.1 billion to 2.1 billion.

- Most commonly used integer type.

- Default type for integer literals (e.g.,

42is anint).

int count = 42;

int population = 1_000_000; // underscores for readabilitylong

- Size: 64-bit signed integer.

- Range: extremely large (~9.22e18).

- Used when integer range of

intis insufficient. - Requires

Lorlsuffix for literals when exceedingintrange.

long big = 10_000_000_000L; // L is important2. Floating-Point Types

Used to represent numbers with fractional parts.

float

- Size: 32-bit IEEE 754 floating-point.

- Precision: about 6–7 decimal digits.

- Use case: large arrays of floating values where memory matters and some precision loss is acceptable.

- Requires

forFsuffix for literals.

float average = 3.14f; // 'f' or 'F' requireddouble

- Size: 64-bit IEEE 754 floating-point.

- Precision: about 15–16 decimal digits.

- Default type for floating-point literals (e.g.,

3.14is adouble). - Most common floating-point type in Java.

double pi = 3.141592653589793;

double result = 1.0 / 3.0;3. char Type

- Size: 16-bit unsigned value.

- Represents a single Unicode character.

- Range: from

'\u0000'to'\uffff'.

char letter = 'A';

char digit = '9';

char unicodeChar = '\u03A9'; // Greek capital letter Omega4. boolean Type

- Represents two values:

trueorfalse. - Commonly used in conditional statements and logical operations.

- No defined size in the Java language specification (implementation-dependent).

boolean isJavaFun = true;

boolean isCold = false;Reference (Non-Primitive) Data Types

Reference types refer to objects stored in the heap. The variable holds a reference (similar to an address) to the object.

1. Classes and Objects

Any class you define is a reference type:

class Person {

String name;

int age;

}

Person p = new Person();

p.name = "Alice";

p.age = 30;- Default value for an uninitialized reference field is

null. - Accessing a member on a

nullreference throwsNullPointerException.

2. String

Stringis a reference type, not primitive.- Strings are immutable.

- Literals are created with double quotes:

"Hello".

String message = "Hello, Java!";

String another = new String("Hello, Java!"); // usually not needed3. Arrays

- Arrays are objects and thus reference types.

- They have a fixed length once created.

int[] numbers = new int[5]; // all elements initialized to 0

int[] values = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}; // array literal

System.out.println(values.length); // 54. Enums

Enums are special reference types representing a fixed set of constants.

enum Day {

MONDAY, TUESDAY, WEDNESDAY, THURSDAY, FRIDAY, SATURDAY, SUNDAY

}

Day today = Day.MONDAY;Enums in Java Overview

Enums in Java are used to represent a fixed set of named constants, making your code safer, more readable, and easier to maintain, especially when you want to restrict possible values a variable can take, such as days of the week, months, colors, or predefined states in a system.

Common Use Cases for Enum in Java

Representing Fixed Categories

Enums help define a set of constant values like days (MONDAY to SUNDAY), levels (LOW, MEDIUM, HIGH), ticket categories (CRITICAL, HIGH, MEDIUM, LOW), or seasons (WINTER, SPRING, SUMMER, AUTUMN).

Control Flow Statements

Enums are widely used in switch-case and if-else statements, for handling logic based on these named values. This improves code clarity and reduces errors from using arbitrary numbers or strings.

Type Safety

They ensure type safety by restricting values to those defined in the enum, unlike traditional final static constants which can be any value.

Grouping Related Constants

Useful for grouping constants related by context, for example, status codes, user roles, or configuration options in applications.

Example of Using Enum

enum TicketCategory {

CRITICAL, HIGH, MEDIUM, LOW;

}

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

TicketCategory category = TicketCategory.HIGH;

switch (category) {

case CRITICAL:

System.out.println("Critical ticket");

break;

case HIGH:

System.out.println("High priority ticket");

break;

case MEDIUM:

System.out.println("Medium priority ticket");

break;

case LOW:

System.out.println("Low priority ticket");

break;

}

}

}

This code demonstrates how enums define constant categories and integrate smoothly with control statements like switch, improving code reliability and readability.

Advanced Use

Enums with Methods and Fields

Enums in Java can have methods, fields, and constructors, enabling them to store and operate on more complex data, such as associating a value or description with each constant.

Interface Implementation

Enums can implement interfaces to provide flexible code design patterns, such as providing descriptions or custom behaviors for each constant.

Conclusion

Overall, enums in Java are preferred whenever you need a variable to accept only a predetermined set of constant values, ensuring code safety and ease of maintenance.

5. Interfaces, Records, and Other Reference Types

- Interfaces define contracts; implementation classes are reference types.

- Records (Java 16+) are special classes for immutable data carriers.

record Point(int x, int y) {}

Point p = new Point(10, 20); // x=10, y=20In Java 16 and later, you can use a record to simplify classes that are mainly data carriers. A record automatically provides private final fields, a constructor, getters, equals(), hashCode(), and toString() methods, which greatly reduces boilerplate code.s

Wrapper Classes and Autoboxing

Each primitive type has a corresponding wrapper class in java.lang:

byte→Byteshort→Shortint→Integerlong→Longfloat→Floatdouble→Doublechar→Characterboolean→Boolean

Autoboxing and Unboxing

Autoboxing is automatic conversion from primitive to wrapper type. Unboxing is the reverse.

Integer a = 10; // autoboxing: int to Integer

int b = a; // unboxing: Integer to int

List<Integer> list = new ArrayList<>();

list.add(5); // autoboxing

int x = list.get(0); // unboxingCommon pitfall: unboxing a null wrapper will throw

NullPointerException.

Integer n = null;

int y = n; // throws NullPointerExceptionType Conversion and Casting

Widening Primitive Conversions (Safe, Implicit)

Small type → larger type, done automatically.

byte → short → int → long → float → doublechar → int → long → float → double

int i = 100;

long l = i; // OK, widening

double d = l; // OK, wideningNarrowing Primitive Conversions (Explicit, Risky)

Large type → smaller type, requires explicit cast and may lose data.

long big = 130L;

byte b = (byte) big; // overflow: result is -126

double v = 3.9;

int k = (int) v; // k = 3, fractional part lostReference Type Casting

You can cast references within an inheritance hierarchy. Incorrect casts cause

ClassCastException at runtime.

Object obj = "Hello";

String str = (String) obj; // OK

Object obj2 = Integer.valueOf(10);

String s = (String) obj2; // ClassCastException at runtimeDefault Values

Default values apply to fields (instance or static), not to local variables.

byte, short, int, long→0float, double→0.0char→'\u0000'boolean→false- Any reference type →

null

class Example {

int number; // default 0

boolean flag; // default false

String text; // default null

}Local variables must be initialized before use or the code will not compile.

Newer Language Features Related to Types (Recent Java Versions)

While the primitive data types themselves have not changed, newer Java versions added features that affect how types are used and inferred.

1. Local Variable Type Inference (var, Java 10+)

Java allows var for local variables, where the type is inferred by the

compiler.

Important: the variable still has a static type; var is

not dynamic typing.

var n = 10; // inferred as int

var text = "Hello"; // inferred as String

// Still type-safe:

text = 20; // compile-time error2. Text Blocks for Strings (Java 13+)

Multi-line string literals using """ are still String type.

String json = """

{

"name": "Alice",

"age": 30

}

""";3. Records (Java 16+)

Records provide a concise syntax for classes that are mainly data carriers.

record User(String name, int age) {}

User u = new User("Bob", 25);

String name = u.name();

int age = u.age();4. Pattern Matching for instanceof (Java 16+)

Makes type checking and casting more concise.

Object obj = "Hello";

if (obj instanceof String s) {

System.out.println(s.toUpperCase());

}Common Exceptions Related to Data Types

NullPointerException- Occurs when accessing a member or method on a

nullreference.

String s = null; int len = s.length(); // NullPointerException- Occurs when accessing a member or method on a

ClassCastException- Occurs when an invalid type cast is performed on a reference.

Object obj = Integer.valueOf(10); String s = (String) obj; // ClassCastExceptionNumberFormatException- Occurs when converting a string to a numeric type fails.

int n = Integer.parseInt("abc"); // NumberFormatExceptionArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException- Occurs when accessing an array index outside its bounds.

int[] arr = {1, 2, 3}; int x = arr[3]; // ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException, valid indexes: 0..2ArithmeticException- Commonly occurs on integer division by zero.

int a = 10; int b = 0; int c = a / b; // ArithmeticException: / by zero

Most Commonly Mistaken Concepts About Java Data Types

1. == vs equals()

==compares references for objects (same memory location).equals()compares contents (if properly overridden).

String a = new String("Java");

String b = new String("Java");

System.out.println(a == b); // false (different objects)

System.out.println(a.equals(b)); // true (same content)2. Treating String as a Primitive

Stringis not primitive; it is a class injava.lang.- It behaves like a value in many scenarios, but it's still a reference.

3. Floating-Point Precision

floatanddoubleare imprecise for some decimal values.- Use

BigDecimalfor precise financial calculations.

double x = 0.1 + 0.2;

System.out.println(x); // may print 0.300000000000000044. Integer Division

- Dividing two integers performs integer division, discarding the fractional part.

int a = 5;

int b = 2;

int c = a / b; // 2, not 2.5

double d = a / b; // 2.0, still integer division first

double correct = a / 2.0; // 2.55. Overflow and Underflow

- Primitive integer types (

byte,short,int,long) overflow silently.

int max = Integer.MAX_VALUE; // 2147483647

int overflow = max + 1; // -2147483648 (wraps around)6. Confusing char with String

charuses single quotes,Stringuses double quotes.charis a single 16-bit code unit,Stringis a sequence of characters.

char c = 'A';

String s = "A";7. Assuming Arrays Grow Dynamically

- Arrays in Java have fixed length.

- To have dynamic growth, use collections like

ArrayList.

int[] arr = new int[3];

// arr.length is always 3

List<Integer> list = new ArrayList<>();

list.add(1);

list.add(2);

// list size can grow dynamically8. Misusing Autoboxing and Caching

Wrapper classes cache some values (e.g., Integer from -128 to 127),

which can lead to confusion when using ==.

Integer x = 127;

Integer y = 127;

System.out.println(x == y); // true (cached)

Integer m = 128;

Integer n = 128;

System.out.println(m == n); // false (different objects)

System.out.println(m.equals(n)); // true9. Thinking var Means Dynamic Typing

vardoes not mean the type can change.- Type is inferred once at compile time and cannot change later.

Best Practices When Working with Data Types in Java

- Prefer

intanddoublefor general numeric work unless you have a specific reason to use others. - Use

longfor large ranges (e.g., IDs, timestamps). - Use

BigIntegerandBigDecimalfor very large numbers or precise decimal arithmetic. - Avoid excessive autoboxing in performance-critical code (e.g., in loops) to reduce object creation.

- Always check for

nullbefore unboxing wrapper types. - Use

equals()to compare object content (especiallyString), not==. - Be cautious with floating-point equality comparisons; use tolerances (epsilon) instead.

- Initialize local variables before use; do not rely on defaults.

Summary

Java data types are divided into primitive and

reference types.

Understanding their sizes, ranges, default values, conversions, and common pitfalls is

essential for writing correct and efficient Java programs.

While newer Java versions have introduced features like var, records, text

blocks, and pattern matching, the core set of primitive types remains unchanged.

Variables

In Java, a variable is a named storage location in memory that holds a value. Java is statically typed, which means every variable has a declared type known at compile time.

Key Characteristics of Java Variables

- Each variable has a name, a type, and a value.

- Type determines what operations can be performed on the variable.

- Variables have scope (where they are visible) and lifetime (how long they exist).

- Java variables must be declared before use.

Basic Syntax

<type> <variableName> [= initialValue] ;

int count;

int age = 25;

String name = "Alice";- Declaration: tells the compiler the type and name of the variable.

- Initialization: gives the variable an initial value.

Classification of Variables

By Data Type

- Primitive type variables – hold primitive values like

int,double,boolean, etc. - Reference type variables – hold references (addresses) to objects

(e.g.,

String, arrays, custom classes).

By Scope / Where They Are Declared

- Local variables – declared inside methods, constructors, or blocks.

- Parameter variables – declared in method or constructor parameter lists.

- Instance variables (fields) – non-static fields declared in a class.

- Static variables (class variables) – fields declared with

static.

Local Variables

Local variables are declared inside methods, constructors, or blocks and exist only within that scope.

void doSomething() {

int x = 10; // local variable

if (x > 5) {

int y = 20; // local to the if-block

System.out.println(y);

}

// y is not visible here

}- No default values – must be initialized before use (otherwise compile-time error).

- Stored on the stack (conceptually) and destroyed when the method finishes.

Parameter Variables

Parameters are variables declared in a method or constructor’s parameter list. They receive values when the method is called.

void greet(String name, int times) { // name and times are parameters

for (int i = 0; i < times; i++) {

System.out.println("Hello " + name);

}

}- Parameters are treated like local variables inside the method.

- They must have a type and a name.

Instance Variables (Fields)

Instance variables belong to an object (instance of the class).

class Person {

String name; // instance variable

int age; // instance variable

void introduce() {

System.out.println("My name is " + name);

}

}- Each object has its own copy of instance variables.

- Default values apply if not initialized explicitly (e.g., 0,

false,null). - Accessible via

this.name, thoughthisis usually optional.

Static Variables (Class Variables)

Static variables belong to the class itself, not to any particular object.

class Counter {

static int count = 0; // static variable

Counter() {

count++;

}

}

Counter c1 = new Counter();

Counter c2 = new Counter();

System.out.println(Counter.count); // 2- Shared among all instances of the class.

- Accessed via class name:

ClassName.variableName. - Useful for constants and shared state (e.g., caches, counters).

Variable Initialization

1. Explicit Initialization

int x = 10;

String message = "Hello";2. Default Initialization (Fields Only)

class Example {

int n; // default 0

boolean flag; // default false

String text; // default null

}Local variables do not get default values and must be initialized before use.

3. Multiple Declarations

int a, b, c;

int x = 1, y = 2, z = 3;For clarity, it is often better to declare one variable per line.

Final Variables (Constants)

A final variable can be assigned only once.

final int MAX_SIZE = 100;

final String APP_NAME = "MyApp";- After assignment, the value cannot be changed.

- For reference types, the reference cannot change, but the object it points to may be mutable.

final List<String> list = new ArrayList<>();

list.add("A"); // OK, modifying the object

// list = new ArrayList<>(); // Error: cannot assign a value to final variableBlank Final Variables

Final variables that are declared but not initialized immediately, typically assigned in the constructor.

class User {

final String id; // blank final

User(String id) {

this.id = id; // must be assigned here

}

}Effectively Final Variables

A variable is effectively final if it is assigned only once, even

without the final keyword.

This is important for anonymous classes and lambdas.

void test() {

int base = 10; // effectively final

Runnable r = () -> System.out.println(base); // allowed

}Local Variable Type Inference (var, Java 10+)

Java supports local variable type inference using var for

local variables

with initializers. The type is inferred by the compiler.

var number = 10; // inferred as int

var text = "Hello"; // inferred as String

var list = new ArrayList<String>(); // inferred as ArrayList<String>varcan only be used for local variables, for-each variables, and traditional for-loop indices.- Cannot be used for fields, method parameters, or return types.

- Variable still has a single, static type – Java is not dynamically typed.

- Requires an initializer (you cannot write just

var x;).

// Invalid uses:

var x; // Error: cannot use 'var' without initializer

var nothing = null; // Error: cannot infer type from null aloneNaming Variables

- Use camelCase for variables and methods:

totalAmount,userName. - Use UPPER_SNAKE_CASE for

static finalconstants:MAX_VALUE. - Names must start with a letter,

$, or_, and can contain digits after that. - Avoid using

$and_unless you have a special reason. - Must not be a Java keyword (like

int,class,for).

Scope and Lifetime

1. Block Scope

if (condition) {

int a = 10; // a is visible only inside this block

}

// a is not visible here2. Method Scope

Local variables declared in a method are not visible outside that method.

3. Class Scope

Instance and static variables are visible to all methods of the class (subject to access modifiers).

Shadowing

A local or parameter variable can shadow a field with the same name.

Use this to refer to the field.

class Example {

int value;

Example(int value) {

this.value = value; // 'this.value' is the field, 'value' is parameter

}

}Variables and Memory

- Local variables and parameters live on the stack (conceptually) and are destroyed when the method returns.

- Instance and static variables are part of objects or class metadata stored on the heap.

- Reference variables hold an address pointing to an object on the heap.

Common Errors and Exceptions Related to Variables

Compile-Time Errors (Not Exceptions)

- "variable might not have been initialized" – using a local variable before assigning a value.

- "cannot find symbol" – using a variable name that is out of scope or not declared.

- "variable x is already defined in method" – declaring two variables with the same name in the same scope.

void example() {

int x;

// System.out.println(x); // Error: variable x might not have been initialized

}Runtime Exceptions (Caused by Incorrect Use of Variables)

- NullPointerException – using a reference variable that is

null. - ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException – using an array index outside the valid range.

- ClassCastException – incorrect casting of objects referenced by variables.

String s = null;

s.length(); // NullPointerException

int[] arr = new int[3];

arr[3] = 10; // ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsExceptionMost Commonly Mistaken Concepts About Variables in Java

1. Java Is Pass-by-Value (Always)

Many people think objects are passed by reference. In reality, Java passes the value of the reference (a copy of the reference).

void modify(int x) {

x = 10;

}

void modify(StringBuilder sb) {

sb.append(" world");

}

int a = 5;

modify(a);

System.out.println(a); // still 5

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder("Hello");

modify(sb);

System.out.println(sb); // Hello worldChanging the reference variable itself does not affect the caller, but modifying the object it points to does.

2. Confusing = with ==

=is assignment.==is comparison.

3. Using == for Strings and Objects

== compares whether two reference variables point to the same

object,

not whether their values are equal. Use equals() for value equality.

String a = new String("Java");

String b = new String("Java");

System.out.println(a == b); // false (different objects)

System.out.println(a.equals(b)); // true (same content)4. Assuming Local Variables Have Default Values

Local variables must be initialized before use; there are no automatic defaults.

5. Misunderstanding static vs Instance Variables

- Static variables are shared across all instances.

- Instance variables are unique to each object.

Accidentally using static variables for per-object state leads to bugs.

6. Thinking var Makes Java Dynamically Typed

- With

var, the compiler still decides a single, fixed type at compile time. - You cannot assign a different type later.

var x = 10; // int

// x = "Hello"; // Error: incompatible types7. Variable Shadowing Confusion

Forgetting that a local or parameter variable shadows a field can lead to unexpected behavior.

class Demo {

int value = 5;

void setValue(int value) {

value = value; // assigns parameter to itself, field unchanged

}

}Correct version uses this:

void setValue(int value) {

this.value = value; // assigns parameter to field

}Newer Language Features Related to Variables

1. var (Java 10+)

- Reduces verbosity in local variable declarations.

- Particularly useful with generics and complex types.

2. Pattern Variables in instanceof (Java 16+)

Pattern matching introduces pattern variables that combine type tests and casts.

Object obj = "Hello";

if (obj instanceof String s) { // s is a pattern variable

System.out.println(s.toUpperCase());

}3. Pattern Matching for switch (Newer Java Versions)

Enhanced switch expressions and pattern matching introduce variables bound

in

case labels, making code more expressive while still being statically

typed.

Best Practices for Variables in Java

- Use meaningful names that clearly describe the purpose of the variable.

- Keep variable scope as small as possible to reduce bugs and improve readability.

- Prefer immutable variables where possible (

finaland effectively final). - Avoid using magic numbers; use constants

(

static final) instead. - Initialize variables close to where they are used.

- Be careful with static variables; overuse can lead to tight coupling and hidden dependencies.

- Use

varwhen it improves readability, not just to save typing.

Summary

Variables in Java are fundamental building blocks that represent named storage locations

associated with types.

Understanding the different kinds of variables (local, parameter, instance, static),

their scope, lifetime,

initialization rules, and how they interact with newer language features like

var and pattern matching

is essential to writing clean, correct, and maintainable Java code. Many common bugs

arise from misunderstandings

about variable scope, initialization, and object references, so paying attention to

these details is critical.

Type Casting in Java

Type casting in Java means converting a value of one data type into another compatible data type. There are two main categories:

- Primitive casting (between

int,double, etc.) - Reference casting (between classes in the same inheritance hierarchy)

1. Primitive Type Casting

1.1 Widening Casting (Automatic / Implicit)

Small type → bigger type. This is safe and done automatically by Java.

Order: byte → short → int → long → float → double

int i = 10;

double d = i; // int to double (automatic)

long l = i; // int to long (automatic)1.2 Narrowing Casting (Manual / Explicit)

Bigger type → smaller type. This can lose data, so you must cast

explicitly

using (targetType).

double d = 9.7;

int i = (int) d; // i = 9, fractional part is lost

long big = 130L;

byte b = (byte) big; // overflow, b = -126Syntax:

<targetType> variable = (<targetType>) value;1.3 Common Examples

float f = 3.14f;

double d = f; // widening, OK

double x = 3.99;

int y = (int) x; // narrowing, need (int)

short s = 100;

byte bb = (byte) s; // narrowing, need (byte)1.4 Casting vs Parsing (for Strings)

You cannot cast a String directly to a number. Use parsing

methods:

String s = "123";

// int n = (int) s; // ❌ compile error

int n = Integer.parseInt(s); // ✔ correct

double d = Double.parseDouble("3.14");2. Reference Type Casting (Objects)

For reference types, you can cast only within the same inheritance hierarchy. There are two concepts:

- Upcasting – child → parent (implicit)

- Downcasting – parent → child (explicit, may fail at runtime)

2.1 Upcasting (Safe, Automatic)

class Animal {

void speak() { System.out.println("Animal"); }

}

class Dog extends Animal {

void bark() { System.out.println("Woof"); }

}

Dog d = new Dog();

Animal a = d; // upcasting: Dog → Animal (automatic)

Upcasting is always safe because a Dog is an Animal.

2.2 Downcasting (Manual, Can Throw Exception)

Downcasting means casting a parent reference back to a child type. You must do it

explicitly, and it

can throw ClassCastException if the actual object is not of that type.

Animal a = new Dog(); // upcast

Dog d = (Dog) a; // downcast, OK at runtime

Animal a2 = new Animal();

// Dog d2 = (Dog) a2; // compiles, but at runtime: ClassCastException2.3 Use instanceof Before Downcasting

To avoid ClassCastException, you should check with instanceof:

Animal a = getAnimal(); // returns some Animal

if (a instanceof Dog) {

Dog d = (Dog) a; // safe downcast

d.bark();

} else {

System.out.println("Not a Dog");

}2.4 Pattern Matching instanceof (Newer Java)

Modern Java lets you combine instanceof and cast:

if (a instanceof Dog d) {

d.bark(); // d is already a Dog

}3. Important Notes About Casting

- Casting does not change the variable’s declared type, only the value in that expression.

double d = 5.9;

int x = (int) d; // cast only here

// d is still double, only x is int- You can only cast between compatible types (same hierarchy for objects, numeric types for primitives).

- Casting does not create a new object for reference types; it just treats the same object as another type.

4. Quick Cheat Sheet

- Primitive widening – automatic:

int i = 10; double d = i; - Primitive narrowing – need cast:

double d = 9.8; int i = (int) d; - Upcasting (child → parent) – automatic:

Animal a = new Dog(); - Downcasting (parent → child) – explicit:

Dog d = (Dog) a; - Strings to numbers – use

parseInt,parseDouble, etc., not casting. - Use

instanceofto check before downcasting to avoidClassCastException.

Class 3 - Recording

▶ Watch VideoControl Flow in Programming

Control flow is the order in which individual statements, instructions, or function calls are executed or evaluated in a program. By default, code runs from top to bottom, but control-flow constructs (like if, loops, and switch) let you change that order.

Table of Contents

- Core Concepts

- If Statements

- Loops

- Switch Statements

- Exceptions (Error Handling)

- What Is “Import All”?

1. Core Concepts of Control Flow

Most programs execute in three basic ways:

- Sequential – instructions run one after another.

- Selection (branching) – choose different paths (e.g.,

if,switch). - Iteration (looping) – repeat blocks of code (e.g.,

for,while).

Simple Example (Pseudo-Code)

// Pseudo-code example of basic control flow

read age

if (age >= 18) {

print("You are an adult");

} else {

print("You are not an adult");

}

for (i = 0; i < 3; i = i + 1) {

print("Loop iteration: " + i);

}2. If Statements (Selection)

If statements allow your program to make decisions. A condition is evaluated, and if it is true, a block of code is executed; otherwise, it is skipped or an alternative block is run.

Basic Syntax (C / Java / JavaScript Style)

if (condition) {

// code that runs when condition is true

} else {

// code that runs when condition is false

}Else If Chains

int score = 85;

if (score >= 90) {

printf("Grade: A\n");

} else if (score >= 80) {

printf("Grade: B\n");

} else if (score >= 70) {

printf("Grade: C\n");

} else {

printf("Grade: F\n");

}Common Pitfalls / “Exceptions” in Behavior

- Assignment vs comparison: Using

=instead of==in some languages can cause bugs. - Truthiness: In some languages, non-boolean values (like 0, empty strings, null) are treated as false.

- Missing braces: Omitting

{ }can make only one line part of theif, not the whole block you intended.

3. Loops (Iteration)

Loops allow you to repeat a block of code multiple times. They are essential for tasks like processing lists, counting, and waiting for a condition to change.

3.1 For Loop

A for loop is used when you know (or can calculate) how many times you want to repeat.

// C / Java / JavaScript style for loop

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

printf("i = %d\n", i);

}Key Parts of a For Loop

- Initialization – run once before the loop starts (e.g.,

int i = 0). - Condition – checked before each iteration (e.g.,

i < 5). - Update – executed after each iteration (e.g.,

i++).

3.2 While Loop

int count = 0;

while (count < 3) {

printf("count = %d\n", count);

count++;

}3.3 Do-While Loop

int x = 0;

do {

printf("x = %d\n", x);

x++;

} while (x < 3);Breaking and Skipping in Loops

- break – exit the loop immediately.

- continue – skip to the next iteration of the loop.

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

if (i == 3) {

continue; // skip when i is 3

}

if (i == 8) {

break; // stop the loop entirely

}

printf("i = %d\n", i);

}Common Loop “Exceptions” and Pitfalls

- Infinite loops: If the condition never becomes false, the loop never ends.

- Off-by-one errors: Using

<=instead of<(or vice versa) can loop one time too many or too few. - Modifying the loop variable incorrectly: Skipping values or causing unexpected behavior.

4. Switch Statements

A switch statement lets you compare a single value against many

possible cases.

It can be cleaner than a long chain of if / else if / else.

Basic Syntax

int day = 3;

switch (day) {

case 1:

printf("Monday\n");

break;

case 2:

printf("Tuesday\n");

break;

case 3:

printf("Wednesday\n");

break;

default:

printf("Unknown day\n");

break;

}Important Concepts

- case label: A specific value to match against (e.g.,

case 1:). - break: Prevents “fall-through” to the next case.

- default: Code that runs if no case matches.

Fall-Through Behavior

In many languages (like C, C++, Java, JavaScript), if you omit break,

execution continues into the next case. This can be useful but also a common source

of bugs.

5. Exceptions (Error Handling Control Flow)

Exceptions are an additional type of control flow used for handling errors or unusual situations. Instead of returning error codes, an exception can be “thrown” and then “caught” by a special block of code.

Basic Example (Java-like Syntax)

try {

int result = 10 / 0; // this will cause an error (division by zero)

System.out.println("Result: " + result);

} catch (ArithmeticException e) {

System.out.println("Error: " + e.getMessage());

} finally {

System.out.println("This always runs (cleanup, closing files, etc.)");

}6. What Is “Import All”?

“Import all” usually refers to importing everything (all functions, classes, variables) from a module or package into the current scope. This is more about module organization than control flow itself, but it influences how code is accessed and executed.

Examples in Different Languages

Python

# Import everything from the math module into the current namespace

from math import *

print(sqrt(16)) # sqrt is available directlyJavaScript (ES Modules)

// Import everything from 'utils.js' as an object called utils

import * as utils from './utils.js';

console.log(utils.add(2, 3));Java

// Import all classes from java.util package

import java.util.*;

public class Example {

public static void main(String[] args) {

ArrayList<String> list = new ArrayList<>();

}

}Pros and Cons of Import All

Pros

- Convenient: You do not need to list every single item you use.

- Shorter code in small scripts or quick experiments.

Cons

- Name conflicts: If two modules define the same name, “import all” can cause collisions.

- Less readable: It becomes harder to see where a function or class comes from.

- Potential performance or bundle-size issues: In some environments, importing everything may load more code than necessary.

Best Practice: Import only what you need, or import using a

namespace (like import * as utils), to keep code clear and

maintainable.

Debugging Basics (Using IntelliJ IDEA)

Debugging is the process of finding and fixing errors (bugs) in your code. IntelliJ IDEA provides a powerful debugger that lets you pause your program, inspect variables, run code step-by-step, and understand exactly what is happening.

1. Core Debugging Concepts

Important terms you will see when debugging:

- Breakpoint – a marker in your code where the debugger will pause execution.

- Call stack – the list of methods/functions that have been called to reach the current point.

- Step over – run the current line and go to the next one (skips inside method bodies).

- Step into – move into the method being called on the current line.

- Step out – finish the current method and return to the caller.

- Watch – a variable or expression that you keep an eye on while debugging.

- Evaluate expression – run small pieces of code during a pause to inspect behavior.

2. Setting Up & Running in Debug Mode (IntelliJ IDEA)

2.1 Create a Run/Debug Configuration

- At the top-right of IntelliJ, locate the run configuration dropdown.

- Click it and choose Edit Configurations....

-

Create a new configuration (for example, Application for Java):

- Set the Main class (the class with

main()). - Choose the correct Module or classpath.

- Set the Main class (the class with

- Click Apply and OK.

2.2 Run in Debug Mode

There are two main ways to start debugging:

- Use the bug icon next to the run configuration (top-right). This starts your program in debug mode.

- Right-click a file (like your main class) in the Project view and choose Debug '<ClassName>'.

When your program hits a breakpoint, IntelliJ will open the Debug tool window at the bottom, and execution will pause.

3. Breakpoints

Breakpoints are the primary tool for debugging: they tell the debugger where to pause so you can inspect what is happening.

3.1 Adding & Removing Breakpoints

- Open the file you want to debug.

- Click in the left gutter (the gray area to the left of the line numbers) beside a line of code.

- A red dot appears: this is your breakpoint.

- Click the red dot again to remove the breakpoint.

3.2 Enabling / Disabling Breakpoints

- Right-click the breakpoint and uncheck Enabled to temporarily disable it.

- Disabled breakpoints turn into a hollow icon but are kept for later use.

3.3 Viewing All Breakpoints

Press Ctrl+Shift+F8 (or use the menu Run > View Breakpoints...) to see and manage all breakpoints in your project.

4. Debug Controls (Step Over, Step Into, Step Out)

When your program pauses at a breakpoint, you control the flow using the toolbar in the Debug window. The icons and names may vary slightly, but the main actions are:

- Resume Program – continue running until the next breakpoint or program end.

- Step Over – execute the current line, but do not go inside methods; move to the next line in the same method.

- Step Into – if the current line calls a method, jump inside that method and pause at its first line.

- Step Out – finish the current method and return to the caller.

- Stop – end the debugging session.

4.1 When to Use Each

- Use Step Over when you trust a method and just want to see its effect, not its internal details.

- Use Step Into when you suspect the bug is inside the method being called.

- Use Step Out when you realize you went too deep and want to go back to the higher-level code.

5. Inspecting Variables & Expressions

The main power of debugging is seeing the state of your program while it runs. IntelliJ gives you several ways to inspect data when execution is paused.

5.1 Variables View

- In the Debug tool window, there is a Variables (or similar) pane that shows all local variables.

- Expand objects (using the small triangle) to see their fields.

- Collections and arrays can be expanded to see their elements.

5.2 Hover Inspection

Move your mouse over a variable in the editor while in debug mode. IntelliJ displays a pop-up with the current value of that variable.

5.3 Watches

Use Watches when you want to track specific expressions or variables:

- Open the Watches tab/panel in the Debug window.

- Click the + icon to add a new watch.

- Type an expression (e.g.,

myList.size()oruser.getName()). - Now IntelliJ will always show the current value whenever execution is paused.

5.4 Evaluate Expression

Evaluate Expression lets you execute code while paused to test logic or inspect state:

- When paused at a breakpoint, click the Evaluate Expression button in the Debug window (often a calculator icon).

- Type any valid expression that can be compiled in the current context.

- Press Evaluate to view the result.

This is very useful for quickly checking conditions, method results, or exploring new code without changing your source files.

6. Conditional & Log Breakpoints

Sometimes you only want to pause or log output when a certain condition is met. IntelliJ supports conditional breakpoints and log breakpoints.

6.1 Conditional Breakpoints

- Right-click an existing breakpoint (red dot in the gutter).

- In the popup, find the Condition field.

- Enter an expression that returns a boolean (e.g.,

i == 10oruser == null). - Now the program will only pause at this breakpoint when the condition is true.

6.2 Log Breakpoints (Without Stopping)

- Right-click a breakpoint.

- Check options like Log message to console or Evaluate and log.

- Uncheck Suspend if you do not want the program to pause.

- Your program will continue to run, but IntelliJ will print debug messages to the console, which is useful for tracing execution without stopping.

7. Debugging Exceptions

Exceptions often indicate bugs or unexpected situations. IntelliJ can help you understand where and why an exception occurred.

7.1 When an Exception Occurs

- If an uncaught exception is thrown, the debugger will pause at the line where it happened (if you are in debug mode).

- The Frames or Call Stack tab will show you the chain of method calls that led to the error.

- The Variables tab will show you the values of variables at the moment of failure.

7.2 Exception Breakpoints

- Open the View Breakpoints... dialog (e.g., Ctrl+Shift+F8).

- Click the + icon and choose Java Exception Breakpoint (or similar, depending on language).

- Select an exception class (e.g.,

NullPointerException,IOException). - IntelliJ will now pause whenever that exception is thrown, even if it is later caught, so you can see exactly where it originates.

8. Example Debugging Workflow

Here is a simple example using Java, but the general idea is similar for other languages.

8.1 Sample Code

public class DebugExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int[] numbers = {1, 2, 3};

int index = 0;

while (index <= numbers.length) { // bug: should be < instead of <=

int value = numbers[index];

System.out.println("Value: " + value);

index++;

}

}

}8.2 Steps to Debug in IntelliJ IDEA

- Set a breakpoint on the line

int value = numbers[index];. - Start the program in Debug mode.

- When execution pauses at the breakpoint:

- Check index and numbers.length in the Variables window.

- Use Step Over to go through the loop iterations.

- Watch how index changes on each iteration.

-

When index becomes equal to numbers.length, the

next iteration will cause an

ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException. You will see the exception and the incorrect condition:index <= numbers.length. - Fix the bug by changing the condition to

index < numbers.length. - Run the program again to confirm it works correctly.

9. Tips & Common Mistakes in Debugging

9.1 Tips

- Start by reproducing the bug reliably (same inputs, same steps).

- Use breakpoints near where you suspect the problem is, not random places.

- Inspect actual values instead of guessing what they might be.

- Use Evaluate Expression to test hypotheses without editing code.

-

Use log breakpoints instead of adding and removing many temporary

System.out.println()orconsole.log()statements.

9.2 Common Mistakes

- Forgetting to run in Debug mode (using Run instead of Debug).

- Placing breakpoints in code that never actually runs.

- Changing code but not rebuilding / rerunning before testing again.

- Ignoring the call stack, which often clearly shows where things went wrong.

- Assuming a variable has one value without checking it in the debugger.

With practice, using IntelliJ IDEA's debugger will become a normal part of your development process, helping you understand your code more deeply and find bugs much faster.

Summary: Debugging with IntelliJ IDEA is about using breakpoints, stepping through code, inspecting variables, and understanding exceptions. Mastering these basics will make you much more efficient at tracking down and fixing bugs.

Comments & Formatting

/** ... */) documents APIs and can be generated into HTML.